A Profound and Unprecedented Reset

Dec 12, 2023

View Maëlle Gavet's End-of-Year Letter as a PDF.

As a lifelong fan of science fiction, I found the rise of generative artificial intelligence over the last 12 months an irresistible story. We are starting to live in a world where the realms of ‘practical’ sci-fi are becoming an everyday reality, and we are still only in the foothills of this tech-led transformation.

More than 1,000 companies in the Techstars portfolio use AI and/or machine learning as at least a component of their business or operations, and we expect to be making scores of investments in AI-enabled startups in the year ahead. However, while AI is already reshuffling the cards across multiple industries, and the impacts will be felt for years, if not decades, to come, I’m focusing this end-of-year letter on another seismic shock: the Great Reset in Venture Capital.

After a sustained 18-month downturn, with venture capital firms (“VCs”) struggling to raise, founders running out of runway, and down rounds spiking – set against a backdrop of interest rates at a 22-year high – nothing in the data, or anecdotally in my own conversations with limited partners (“LPs”), VCs, our corporate partners and Techstars portfolio companies suggests that a rapid V-shaped bounce-back for the technology venture capital industry is on the horizon. On the contrary, we continue to fly somewhat bumpily through thick clouds with no end in sight.

So the question then becomes: are we at the bottom of a cycle which will, in due course, see us return to where we were a couple of years ago? Or is this something different altogether?

My view is that what we’re going through is not cyclical, but a profound and unprecedented reset. The tectonic plates have shifted beneath the VC industry and realigned. The market will not revert to the heady, frothy days of 2021. At least not in the foreseeable future.

In this letter I’m going to give you the Techstars perspective on what this reset will look like, what it means for LPs, VCs and entrepreneurs in 2024. I will also illustrate why Techstars is uniquely positioned amid this ongoing disruption, and how our model of scale combined with hyperdiversity of investments is specifically designed to counteract market volatility.

But, first, let’s remind ourselves how we got here.

2023, The Year of the Dragon – AKA Back to Basics

After the ‘Gold Rush’ of 2021, in which a deluge of FOMO-fueled venture investment in startups reached $638.4B globally, 2022 saw the market plunge by 35% to $415.1B – and that was after a relatively healthy first quarter.

Throughout 2023 we have continued to see a subdued market characterized by investor caution, steep valuation resets, a glacial IPO market, and many LPs now actively skeptical of VC as an asset class with knock-on effects for the entire industry. As of this writing, over the course of the first three quarters of 2023, a total of $193.6B had been invested in startups globally, with a slight uptick in Q3 masking a market that is still essentially on life support.

Source: PitchBook

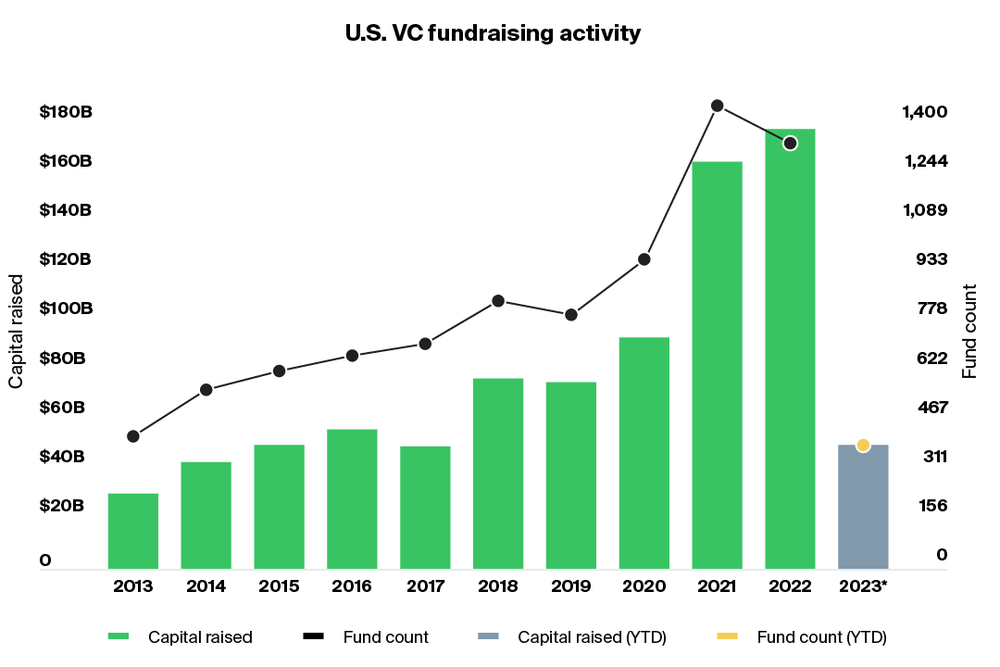

Unsurprisingly, in this climate, U.S. VC fundraising activity and the number of funds actively raising has contracted sharply, with just $42.7B raised by 344 funds (as of Sept. 30, 2023) – the lowest fund count since 2013 – compared with $172.5B raised by 1,278 funds in 2022.

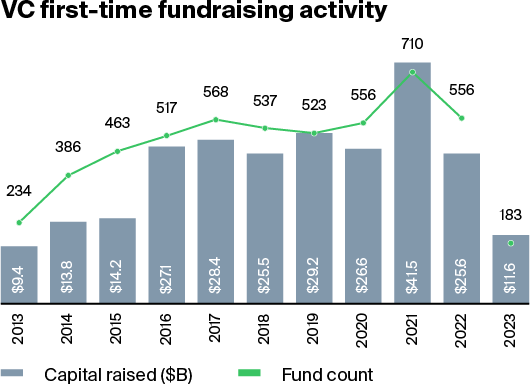

As I suggested in Fortune at the start of the year, one of the biggest themes to have emerged in 2023 is the consolidation that has occurred within the venture capital industry, and the rise of so-called “zombie” VC funds, which effectively operate only to manage existing investments, while being unable to raise fresh capital. This is especially true of emerging managers, who were on track to raise far less this year than they have in a decade, with just $11.6B raised across 183 funds (as of Sept. 30, 2023), compared with $25.6B by 556 funds in 2022 – according to PitchBook, “the lowest annual fundraising total for first-time managers since 2013.”

Source: PitchBook

The impact of all this has been that only the most successful startups, especially those in red hot categories such as AI and climate/sustainability, have been routinely able to raise capital. For those founders unable or unwilling (because it didn’t make sense) to enlist venture support, it has meant building their startup by employing a different model to the hyper-growth and market dominance traditional VC demands: namely, prioritizing resilience and unit economics instead.

I sometimes refer to these startups as “dragons” – a term I prefer to unicorns (companies with $1B+ paper valuations) whose fairytale resonance is the polar opposite to the remorseless grind required to scale a startup. Unlike unicorns, dragons are smaller ($100M+ valuations), independent, tenacious, yet nimble. They build genuine defensive moats, keep a tight grip on spending, and shorn of VC largesse, reach profitability far sooner. Techstars currently has 106 dragons in its portfolio.

2024: The Great Venture Reset

So what will 2024 look like?

The short answer is rather than a prelude to a recovery, 2024 will be much more of the same. Valuations will continue to be real world rather than fantasyland, VCs will raise substantially less than in the times of plenty, and the IPO market will gradually return (largely due to a backlog of companies requiring liquidity and cap table simplification), but not to anything like the feeding frenzy we saw a couple of years ago. Above all the Great Venture Reset means the consolidation of the VC industry is here to stay, and there are likely to be significantly fewer, but higher performing VCs as a result.

Two key reasons underlie this:

1. LPs had a reality check.

Over the past 18 turbulent months, LPs have had a reality check regarding venture capital as an asset class. As returns have fluctuated wildly, many have come to appreciate that despite its obvious attractions (especially the stellar returns of the leading firms and the occasional stratospheric startup success story), venture is an overcrowded space subject to extreme volatility, which makes the 10-year-plus lifespan of a typical fund significantly less appealing than it was during a bull market. They have recalibrated their capital allocation strategy accordingly, with many rejecting or minimizing exposure to venture altogether.

2. ‘Factory-farmed’ unicorns passed their use-by date.

As argued incisively by VC and former Facebook VP Sam Lessin, “the VC ‘factory’ line has shut down and isn’t turning back on. Public demand for factory-farmed unicorns didn’t play out as hoped.”

Lessin writes that over the last 20 years, the venture industry had effectively reorganized itself into a factory production line which took raw, but promising startups at one end and pumped out fully-formed, be-horned unicorns to serve the public markets at the other. “Each stage funded a certain type of development of a company with specific and expected outputs, and fed that product into the next stage - taking the markup along the way.”

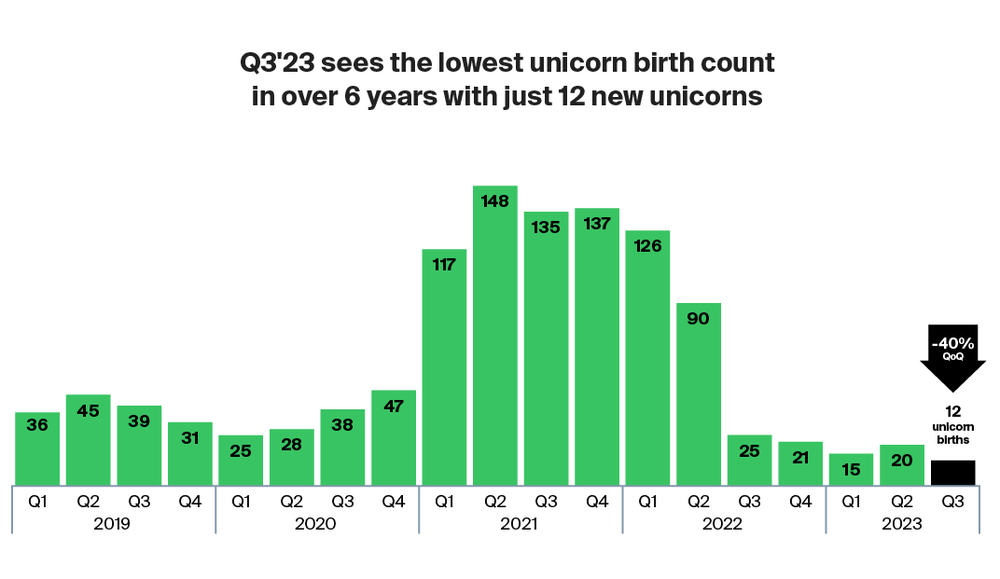

Source: CB Insights

This model peaked in 2020-2021, when money was cheap, VC firms were awash with cash, term sheets were written on the backs of takeaway menus, ‘good enough’ companies were getting funded, and valuations were the stuff of science fiction. But that factory-production approach was always unsustainable and eventually broke down altogether. Significantly, this year saw a dearth of unicorn births, with just 47 created in the first nine months, compared with 262 last year, and 537 in 2021.

On the whole, this is a good thing for the industry: most companies shouldn’t be valued at 30x their revenue. There shouldn’t be a new unicorn minted every day; they should be a rare breed. Venture capital is invaluable for a certain type of business – bluntly, those that can leverage technology to scale rapidly and change a market – but it’s also been terrible (and inappropriate) for many others. Especially those founders, dazzled by the lure of flattering paper valuations, who adopt a VC-fueled scale-at-all-costs approach without a clear pathway to profitability. Not every founder or every business needs to be a unicorn to succeed.

Despite the volume of startups we invest in, Techstars never took the unicorn production line approach to startups. Throughout our highly personalized programs, we emphasize the importance of business fundamentals and financial sustainability, and that fundraising from VCs is a means to an end. Our goal is not solely to churn out startups built on mythical valuations, but to create meaningful, profitable businesses that stand the test of time.

A Healthy Dose of Realism: Five Predictions

The Great Venture Reset is going to take time to solidify – but I am convinced that we will end up with a slimmed down, more effective industry with fewer VC firms, fewer unicorns, more reasonable valuations, and ultimately a greater proportion of successful startups. Crucially new models for funneling cash to startups will also develop, alongside intensifying interest in those accelerators that bolster company fundamentals (as opposed to contributing to the unicorn factory), which we are already seeing at Techstars with applications more than doubling for our 2023 programs.

1. U.S. family offices will increasingly invest directly in startups.

In recent months there has been a growing split between categories of limited partners. Pension funds and endowments have become notably cautious about how much and to whom they allocate in venture, with many rejecting the category altogether. Meanwhile, we have observed that family offices in the U.S., who helped fuel the VC frenzy of 2020-21, are increasingly interested in investing directly in startups rather than going through funds, in addition to generally allocating less to VC overall.

This shift is not just about diversifying assets; it's also about creating a lasting impact and believing that they can outperform VC. A lot of the family offices we talk to at Techstars are increasingly drawn to investments that offer both financial returns and alignment with their core values, particularly in areas like sustainable technology and healthcare. They're seeking a deeper connection with their investments, which goes beyond the merely financial. They're not just passive investors; they want to be part of the story of the companies they invest in, influencing and nurturing them towards success. Often they see their investments as extensions of their legacy.

2. There will be fewer VCs and unicorns.

In these flinty, choppy waters, LPs and institutional investors still allocating to venture will continue to prioritize those few top-tier funds with glittering track records – if they can access them – at the expense of mid-ranking, midsize VCs with average returns, and unproven emerging managers.

As a result, a lot of new business creation will happen without VC cash and that is a good thing. Venture money comes with very specific strings attached – first and foremost expectation of exponential growth. That is not applicable to the majority of businesses. Too many VCs were anyway chasing relatively few outstanding entrepreneurs. If 2023 was the year of consolidation for VC firms, 2024 will see further retrenchment. And far fewer unicorns as a result.

3. Regulatory complexity will become a thing for VCs.

As I’ve argued throughout, VC – an industry predicated upon transforming other verticals at scale – is itself facing significant disruption. But adding fuel to this fire is the recent barrage of legal and regulatory changes, underscoring a new interventionist approach from the authorities.

This includes new merger guidelines introduced by the FTC and DOJ; President Biden's Executive Order, which will impose restrictions on U.S. investments in “countries of concern” in sectors like semiconductors and microelectronics, quantum information technologies and AI; the proliferation of AI initiatives including an updated AI R&D roadmap, the SAFE Innovation for AI framework emphasizing security, accountability, and innovation, and the CREATE AI Act; and California Senate Bill (SB) 54: which will mandate VC firms to report diversity data on the founders they invest in.

Individually these changes make sense and are designed to curb some of the industry’s excesses, the lack of diversity and improve national security. But together they are shifting the ground under the venture industry’s feet, and creating a new tier of regulatory complexity for VCs to navigate.

4. The best accelerators will become more pertinent.

The best accelerators will become especially pertinent in 2024. Just as the number of active VC funds exploded over the past decade, there has been a corresponding boom in accelerator programs; some standalone, the majority spun out of large corporations, financial institutions and universities. Only a fraction of these have stayed the course in a field dominated by a handful of proven players, like Techstars, with the pedigree, rigorous selection process, global network and model honed over the years to produce a steady stream of dragons.

Due to the prevailing climate making it harder for entrepreneurs to raise from traditional VC, combined with mass layoffs in the tech sector which have led many former employees to turn to entrepreneurship, applications to our programs have more than doubled this year, while our quality filter remains as stringent as ever. The value of the programs that Techstars runs is self-evident to both founders and investors. Founders get the entrepreneurial bootcamp, mentorship, and support with fundraising they need, especially in this tightest of markets:

74% of Techstars companies raise capital within three years after their accelerator program, more than any other global accelerator surveyed by Pitchbook (Source: PitchBook)

31% of Techstars companies exit within eight years after their accelerator program, more than any other global accelerator surveyed by Pitchbook (Source: PitchBook)

While for investors, we have built a qualification funnel of pre-vetted startups for seed and series A-stage investors, while enabling LPs to invest in our funds to access a broad range of companies, diversified across multiple sectors, in key startup hubs. This is akin to offering exposure to an actively managed, early-stage index, which minimizes volatility and provides recurring, positive and predictable returns.

5. Alternative venture models will come to the fore.

Legacy VC, as it’s widely understood, has only been meaningfully disrupted once so far, by Andreessen Horowitz who built a platform for entrepreneurs that offered services and support (e.g. HR, marketing, legal) in addition to capital. As venture firms bid to stay relevant to entrepreneurs, we will see more of that platform approach – despite the fact that the unit economics of VC will make it challenging for mid-size and smaller funds.

Additionally, I’m regularly hearing from sources across the industry that platforms serving the VC industry, itself, are being actively considered. Due to the fact that it straddles multiple skills from sourcing to picking to fundraising to negotiating term sheets to managing a small business, VC is hard to do. Platforms that offer VCs, for example, back office support or even fundraising services would allow investors to focus on their core differentiator: sourcing and picking.

Disruption is no longer a buzzword

As a three-time entrepreneur myself I’m a firm believer in the axiom that ‘necessity is the mother of invention’. And it applies equally well to VCs as it does to entrepreneurs.

A couple of years ago, raising yet another fund was a stroll in the park for the average VC. There was plenty of capital to go around, competition was rather less than fierce, and there was scant accountability besides paper valuations. Startups were queueing up to pitch you why they were the next Uber. A new generation of aspiring VCs flocked to the industry in droves. Stories of founders becoming overnight billionaires abounded. The result? Complacency set in. There was very little innovation in the industry, very little experimentation with fresh models, or challenge of the existing dogma, because there didn’t need to be.

It’s a very different market now. In this new normal, disruption is no longer a buzzword but a reality. Every single asset class has undergone consolidation, and VC was long overdue for its own period of contraction. And because it is a business with extremely long cycles, consolidation in VC is far from done. Some firms will disappear, others will try new models, and competitors will rise up. The Great Venture Reset is well underway. Expect a quite different industry to emerge on the other side.